The following article discusses suicide, which some readers may find distressing.

Erin Fitzgerald could always see the signs that she was different growing up – the tools to recognize how simply didn’t exist yet.

“I grew up in an era where mental health was talked about very differently from how it is talked about today. There are some similarities and holdovers, but a lot of differences too,” Fitzgerald, who also identifies as queer and uses she/they pronouns, said. “In the 70s and 80s, I do not remember any conversation around mental health or counseling that did not feel totally pathologized. I do not remember myself or anyone else getting referred to talk with someone or getting assessed for something based on how we were doing or how we were feeling inside. I would only hear about mental health if someone were seen as causing a problem for other people, or seen as a problem themselves.”

Fitzgerald also grew up in a household with a parent who was diagnosed with a severe mental illness, who did not have the same options for support and resources that exist today. “It makes me sad to think about this, because my dad struggled quite a bit and had a hard time finding the right kind of support,” she shared. “He ultimately died by suicide, which is an all-too-common scenario when people do not have the support that they need to address their mental health issues. I cannot help but wonder if he were living in a different time, and if he could have found the kind of support that exists now, how things might have gone differently.”

Fitzgerald, who works with HDI as the CTP Coordinator with HDI’s Supported Higher Education Partnership, has had her own journey with mental health. She has had family that struggled, has worked as a support provider, and has sought support from the system as well. She was given multiple diagnoses before finally being assessed for autism and sensory processing disorder as an adult.

“It wasn’t until some years later that I even heard the term ‘Neurodiversity,’” Fitzgerald said. “That really clicked some things in place for me. It was a turning point for me to think about the way I was wired as being a neurotype and an identity, and not a problem to be solved or a thing to be fixed.”

For Fitzgerald, this was a revelation – and a total reversal of how anything related to mental health was treated in the past.

But the signs were always there, and looking back, Fitzgerald sees them clearly – both in how it’s affected her view of the world at large, and how it’s affected her view of something deeply important to her – art.

“It is interesting – I think that way my brain is wired has always affected my view on the world as well as my art. But I have not always been in good touch with what that wiring was,” Fitzgerald said. “So only in recent years do I feel that I am able to understand the degree to which that affects my view of the world, and how that is portrayed in art.”

That’s a big part of how Fitzgerald relates to the world. Art, she said, is an essential part of her life.

“When it comes down to it, art is the primary way that I process information and emotions. This has always been true, and not just with visual art. Music, writing, theater, any kind of creative expression – it all helps me to process things,” Fitzgerald said. “Consuming it, creating it, engaging with it, talking about it – all of these actions are extremely important to me. I can’t imagine life without being swirled up in the arts on a regular basis.”

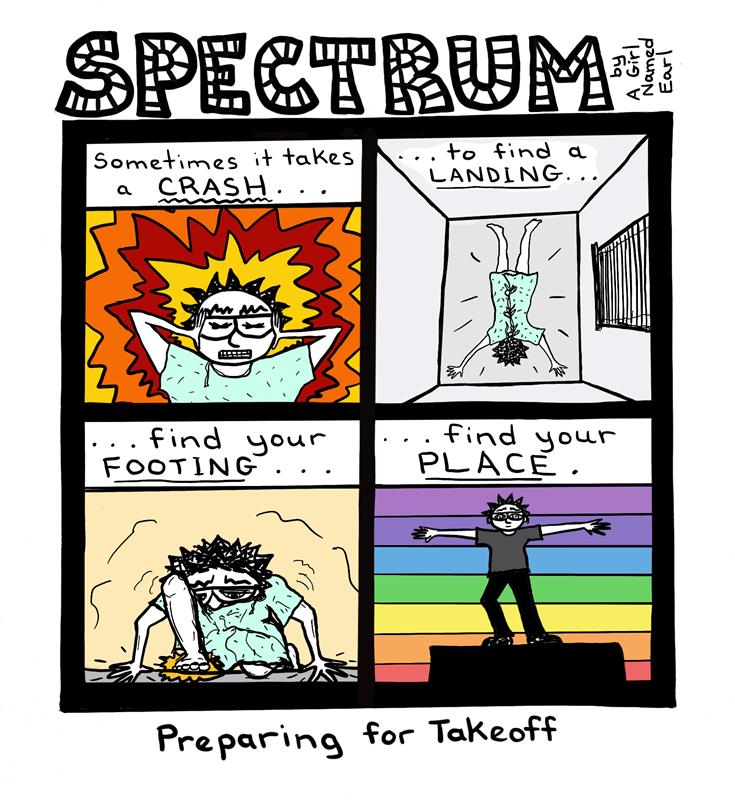

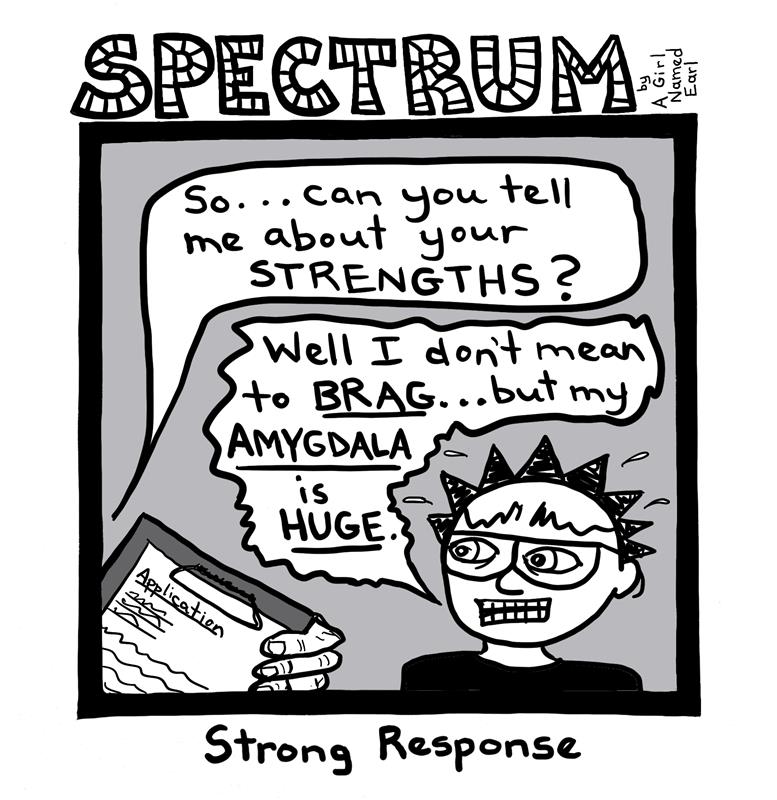

Today, Fitzgerald creates a cartoon called SPECTRUM that explores the multiple aspects of her journey and identity. She started the project after attending a class with Lynda Barry – somewhat accidentally, she noted.

“I did not go there to learn cartooning specifically, but after the workshop I started drawing cartoons every day. I did not set out to draw a cartoon called SPECTRUM, or to cover specific topics such as Neurodivergence and Queerness. But that is what kept coming out on the page, so that is what I went with,” Fitzgerald said. “I have been drawing SPECTRUM cartoons ever since, and it has been a great tool for me to further process the world around me and to think more deeply about my interactions within it. It has also turned out to be a good tool for having conversations with other people around those subjects.”

Cartoons like SPECTRUM are relevant to an emerging field known as Graphic Medicine, one that Fitzgerald says is still finding its identity. But it’s one she finds exciting for its diversity in application and accessibility. Graphic Medicine is, explained simply, the intersection between the realms of graphic arts (such as illustration and comics) and health and medicine. This can take many different forms, which is part of the appeal. It also does something that is central to a lot of work that Fitzgerald does – gives a voice to more people to share their experiences.

“I was drawn to this field for many reasons,” Fitzgerald said. “The part of this field that is most appealing to me is the fact that engaging with and creating graphic works can increase understanding of topics such as overall health, medicine, mental health, identity, and community engagement. It can intersect and therefore help connect people and ideas from all different disciplines and perspectives.”

Fitzgerald also notes that the principles of graphic medicine are in line with those of Universal Design and Universal Design for Learning in a few key ways – in giving people additional tools to communicate and understand concepts related to health and medicine, and in giving a voice to people receiving supports – allowing everyone the chance to learn together. In addition, graphic formats provide context and color to raw data, adding images and stories to the numbers.

Fitzgerald is also working on a wordless graphic memoir called InQuest, which documents her perspective about the mental health system. She hopes the project will help increase understanding of that system from the perspective of people who have navigated it from the other side. “The message I find most important from that project is this: the perspective of a person experiencing a mental health crisis is valid and meaningful, and should not be dismissed,” she said. More information about that project can be found here.

Today, Fitzgerald works with people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) as they attend college – something that has only recently become an option for many. That, Fitzgerald says, is because people have historically not included the voices of people with IDD in conversations about higher education.

“I think this is partly because of that tendency in our society to separate people into categories based on what we are told they do or don’t know, or can or can’t do,” she said. “If we want to be truly inclusive, we need to see everyone else as a partner in this journey, and not only in a specific role of expert or learner. That is how we got here, so we need to expand our own perceptions as we continue to build the way forward.”

In general, that is a uniting factor in a lot of what Fitzgerald does – working to ensure that voices of all people are heard and valued in the process.

“One of the main things I want people to understand about mental health and IDD is that all people offer perspective that is valuable to the rest of the world. In our society, we tend to put certain perspectives up on a pedestal as being more important, and putting other perspectives in a category as being less valued,” she said. “We tend to separate people into categories of those with expertise to share, and those who need that expertise. That is oversimplified and can be quite dangerous. It is important for us to recognize the value in all human perspective, and to stop pathologizing everything that is outside of the norm. I think we have come a long way in this, but we still have a long way to go.”

Read Fitzgerald’s ongoing comic, SPECTRUM, here.