Chelsea Gibbs has only recently started thinking of disability as part of her identity.

“I’m a caregiver for a young lady with an intellectual disability, and she lives with us half the time, and she is struggling with the concept of her having a disability as well,” Gibbs said. “She’s afraid of the word, so we’ve been very pro disability pride, look at all these cool people who do this.”

As she considered this, Gibbs thought about her own history—her diagnoses of OCD, generalized anxiety disorder and depression, as well as a few recently diagnosed chronic illnesses. She hadn’t always considered those diagnoses as disabilities, but upon further reflection, it clicked into place in a way it hadn’t before. She and her wife, Dr. Rachel Womack, who serves as HDI’s Training Director, have had a lot of recent conversations about the intersectionality of disability and queer identities and how people process those identities.

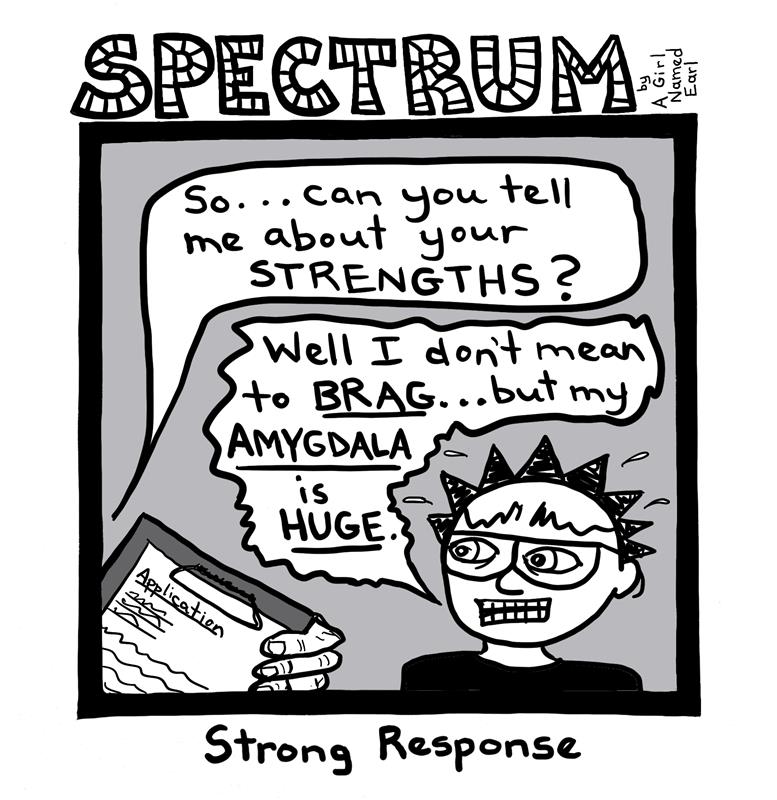

“I’ve actually talked to a lot of people who had a similar experience to Chelsea where maybe they came out as queer in middle school or high school,” Womack said. “Then they’re 20, 30 years old and they’re getting a late-in-life autism diagnosis or a diagnosis of a chronic illness or they’ve acquired a disability… It’s important to think about how the experience of embracing one part of that identity can impact your experience of embracing the other.”

Multiple studies have shown people with disabilities are more likely to identify as queer. Little research has been done on this connection. Womack has been one of the few researchers to explore this oft-ignored intersection of identities, but she says there are still a lot of unanswered questions that Womack and Gibbs hope are one day answered or explored.

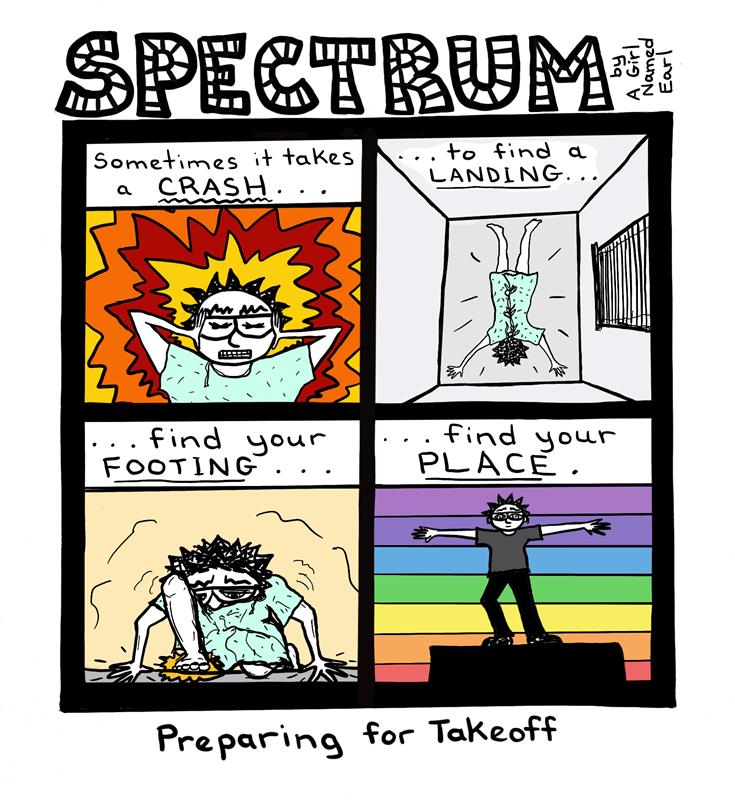

In the meantime, Gibbs notes that living with an intersectional identity can be a complicated experience.

“You have to continually do some deep self-reflection and how you identify is forever changing,” she said. “Who am I? Who are my people? Where am I safe? Am I normal? Who are my friends?”

Womack added just because two groups face marginalization, even if they’re similar forms of marginalization, that doesn’t mean those two groups will be free of negativity towards one another.

“I think some of us have an idea that, [when] going to interact with another marginalized group of people, they probably get it. But that’s not always the case,” Womack said. “There’s certainly some ableism in queer spaces and I think there’s some homophobia and compulsory heterosexuality and things like that in disabled spaces too.”

No matter how complex the identity, though, Womack said it’s simple to be supportive—not just of these particular groups, but for everyone with a marginalized identity.

“Allow them to be fully who they are, however they would like to present that to you,” she said. “That’s everything from if they would like you to use certain pronouns, if they have a chosen name that’s different from their birth name, if they prefer identity-first versus person-first language. It’s having respect for things like that and having respect for those preferences and for those needs, we’re creating safer spaces for people.”

It can also be challenging to deal with situations where people are hostile to some identities, something both Womack and Gibbs have had to deal with during their careers. Womack has a background in social work and Gibbs works as a music therapist. When they encounter hostility due to their identities in those roles, they both agree there is a time and place for advocacy. When they are at work, the client comes first.

Both also feel there are amazing things happening for both the queer community and the disability community, noting meteoric shifts in a relatively short time.

“Just look back ten years ago. [Both] the disability rights movement and the queer movement were in such different place[s]. You couldn’t even get married,” Gibbs said. With those shifts in culture, comes a younger generation that’s more open-minded and accepting.

While there are still a lot of questions about the intersectionality between the disabled and queer experiences, Womack is just one of the researchers ensuring they will have answers.

“There will be [answers],” she said. “Just give me time.”